Between May and July of 2017, the sensitive personal information of 143 million American consumers was exposed in a data breach at Equifax, one of the nation’s three major credit reporting agencies. I was one of them and it’s likely you were too. In this article, we’ll discuss a new paradigm in how we think about email addresses to protect ourselves from future attacks.

The Prologue

On Wednesday, August 30, 2017, Developer Security blogger, Troy Hunt, released an article about a massive 711 million record spambot dump that he helped uncover. Troy is the creator of Have I Been Pwned (www.haveibeenpwned.com), a free site that allows people to enter their email address to discover if it has been found in breached data. People curious why they’ve experienced an influx of spam may venture over to his site to learn whether their email address (and sometimes complete name, password, password hints, username, physical address, IP address, etc.) was listed in the latest Equifax or Yahoo breach, and had been made accessible to a world of spammers and hackers.

While the article is enlightening, I began to realize the underlying issue with how we think about our email address. Victims of security breaches have often been assuaged by the compromised services with calming alerts to inform them that their passwords had been encrypted and they should only change them as a precautionary measure. However, the email address itself is already in nefarious hands and will continue to be bombarded by spoofing attempts, spear-phishing emails, malicious code and viruses, and unprecedented spam. Naturally, email service provider Yahoo, who suffered a breach of 500,000 usernames and passwords in 2012, couldn’t very well recommend that users create brand new Yahoo email addresses. They were smart enough to realize that a considerable number of their customers only continue to use their old Yahoo email address for historical reasons. As such, recommending they re-create a new one would likely trigger users to dump their email service entirely. But Troy also noted that nearly 60% of Yahoo users had the same email address AND PASSWORD as they used for their Sony accounts, a service that suffered a data breach the previous year.

All too often, as in the Yahoo-Sony example above, users carry the same password across multiple services. In an ideal world, the user immediately changes their password — on ALL services that have the compromised password — to a new, unique one for each service. But a more likely scenario is that they either change the password to an identical one across all services or, worse, they only change the password for the compromised site, leaving the remaining exposed and accessible to hackers. Keep in mind, this is only after companies like Yahoo! merely suggest they change a hacked but encrypted password as a precautionary measure, and this deceptive wording may lead a user to believe they needn’t change their password at all.

In a recent article entitled “A Developer’s Guide to Managing Email Accounts,” Mike Citarella encourages us to re-think of how we use email addresses for service identification, organization, and spam prevention. Below, I will make a case for evolving our email usage and mentality for something far more critical and fundamental: our security.

The Old Paradigm

In the past, we’ve gone through the process of creating a new email address, providing personal information for this address, and even verifying the account with a recovery address and phone number. To be extra cautious, we use a brand new password, too, which is likely the same as the previous password, but with a year or a symbol appended to the end. It’s a tedious but necessary process that results in us getting a clean inbox devoid of clutter, and an additional method of communicating with the world. Our previous email addresses will be relegated to weekly or monthly checks, just to make sure we’re not missing anything important, or abandoned altogether. This isn’t the first time we’ve created a new account and it won’t be the last time. We’ve come to think of the nuisance of spam and hacked accounts as the slowly accumulating crud in our car’s oil filter. We may not consider our email to be disposable, but we know it has a shelf-life.

Part of the tedium of this process of changing over our email addresses is updating our online accounts with the new one. After a long day, most of the accounts are updated, with the balance trickling in weeks and months later, after repeated checks to our old, retired addresses. For the time-being, we’re happy.

Part of the tedium of this process of changing over our email addresses is updating our online accounts with the new one. After a long day, most of the accounts are updated, with the balance trickling in weeks and months later, after repeated checks to our old, retired addresses. For the time-being, we’re happy.

Inevitably, spam begins to arrive. We check Have I Been Pwned, only to find out that one of the services with the newly migrated email address has been breached and our data has been exposed again. It’s time to start over, frustratingly sooner than we expected. The JiffyLube sticker’s ink on our dashboard is still fresh.

The Repercussions

Naturally, users aren’t going to create different email addresses for every online service. This would be a lot of email addresses to create and a lot of inboxes to check. And if we’ve listened to Edward Snowden, and we’re cautious about our security, it would also be a lot of different passwords to try to remember.

We also know that along with the aggravation of creating new email addresses, by the time we’ve learned of the compromised service, the damage is already done. Ignoring the fact that the breached site could contain extremely personal information, like a bank account, credit bureau, or online finance application, much of the personal data we provided when we created the email address itself has already been stolen. This involves information that’s far less changeable like password hints that are used across multiple services: mother’s maiden name, father’s middle name, place of birth, etc.

Using the same email address, regardless of password, may still have astonishing ramifications. Users who only provide a phone number for verification on a hacked email account may not realize that hackers now have two pieces of information they can use for identity theft. If they’re clever, they’ll use this confidential data on sites with more personal information — coupled with a DDoS attack to ascertain passwords — and quickly get access to credit card numbers, social security numbers, birth dates, etc. It could take months, even years, to repair the damage created by one seemingly benign hacked email address.

The New Paradigm

The solution to the above scenario involves the next step beyond simply creating a new email address. It’s actually changing the paradigm of how we think about an email address in the first place. In the past, we’ve thought about the inbox as a mailbox, the email address as box number, and the password as the key. We had no problem providing the box number to the public, so long as the key was well-guarded.

In the new paradigm, we should try to think of missile defense systems in the movies, where two highly decorated generals, across a broad blinking control panel, simultaneously slide-in their keys, turn them, place their thumbs on two identical thumbprint scanners, and trigger the launch buttons. Your email address is one thumbprint scanner. Your password is another.

If we safeguard our actual email address from the public, the same way we’ve always guarded our passwords and mailbox keys, we’ve created a far more impenetrable mailbox. Imagine a spammer or hacker attempting to fill your PO Box with malicious mail when he doesn’t have an address to write on the envelopes. This is uniquely possible by using something called an email forwarder.

Email Forwarders

Think of email forwarders like those USPS relay mailboxes on street corners. There’s no slot, the contents and addresses are hidden inside, and postal workers use them to route mail to your actual mailbox.

Email Forwarders are unidirectional addresses that may only forward the mail that they receive. They’re not mailboxes and cannot store messages. They can’t be used for outgoing mail or for replies. They simply relay emails. Some hosting services provide email forwarders free-of-charge and range in the number you can create for your hosted accounts. A few email hosting services offer forwarders as well. iCloud, for instance, allows three. There are also a number of online services that offer nothing but email forwarding, often for a nominal fee and up-sell you by providing other bells and whistles. Here’s a link to a list of them: www.privacy-emails.info

Following the creation of a new email address, rather than providing it to online services, users create forwarders for these services, instead. If you want to sign-up for Facebook, you would create a forwarder just for Facebook. If you want to sign-up for a bank account or a credit card, you would create an email forwarder that you would specifically use for that bank account or that credit card. Everybody gets a forwarder; nobody gets your email address. In the new paradigm, remember, your email address should be treated with the same secrecy as your password.

Now, if one of these online services is breached, the only information they have is a forwarder. The forwarder isn’t tied to any other online service and it cannot be traced back to your private email address. Simply update the forwarder and password on the one compromised account, block the previous forwarder, and your work is done. There’s no reason to create a new email address or to worry about other online services being affected by the breach. Spam and phishing emails sent to the blocked forwarder will be deleted automatically rather than delivered to your inbox. And users who recognize common forwarding services won’t fall victim to spoofing attempts as they know email forwarders can only receive mail, not send it.

Those who wish to illegally access others’ personal information have been playing dirty for decades. Their intent has grown far beyond the simple annoyance of spam. With the transmission of viruses and malware, and the rampant practice of identity theft and credit card forgery, it’s beyond time for us to level the playing field.

I encourage those readers who are skeptical to give this solution a try. If you host your own mail, contact the provider to learn how to create forwarders. If you use an online mail provider, search their knowledgebase about their offering, or take a look at the link above to research email forwarding services.

Bulc Club is Free!

In the interest of full disclosure, I’m a co-founder of Bulc Club (bulc.club). Bulc Club is an entirely free service that offers unlimited email forwarders and mail filtering based on our members’ ratings. The added benefit of Bulc Club, beyond other email forwarding services, is that forwarders are created automatically the first time they’re used.

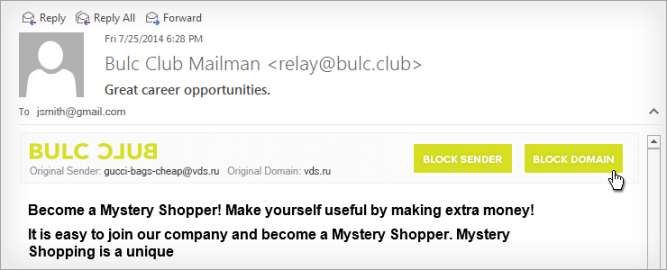

Figure 2. Bulc Club information panel with block buttons

Additionally, at the top of every email that Bulc Club delivers, we include a small header with information and links about the sender. In the event that spam slips through our filters, members can easily view the originating email address and mail server domain to detect spoofing attempts and click the links to report and block the spammer. This simple click increases the member rating and helps prevent this spammer’s messages from being delivered all other members. The more members we have, the less likely you’ll ever see a spam message again. Our members have already identified and blocked countless spammers and, with each new member, we’re more determined to rid the world of spam, once and for all.

Bulc Club is a labor of love, created to help the world understand the new paradigm of email addresses and level the playing field against spammers and hackers. It’s 100% free and we’d love your help. Start protecting your email address and your privacy.

This article was originally printed on September 20, 2017, on Medium.com